War and Disaster―Expression of Ordinary Life

From February 18th to 25th I visited Poland with Yumi Yoshikawa, the organizer of ENVISI, who is also a contributing writer for this website. She helped me with a Miniami-sanriku screening of Storytellers (2013 © silent voice)―part of a trilogy of Tohoku documentary pieces by Ko Sakai and Ryusuke Hamaguchi. And out of the blue, in the Minami-sanriku hotel we were staying on the night of the screening, she asked; “Do you want to go to Auschwitz?”

I had no hesitation in saying yes.

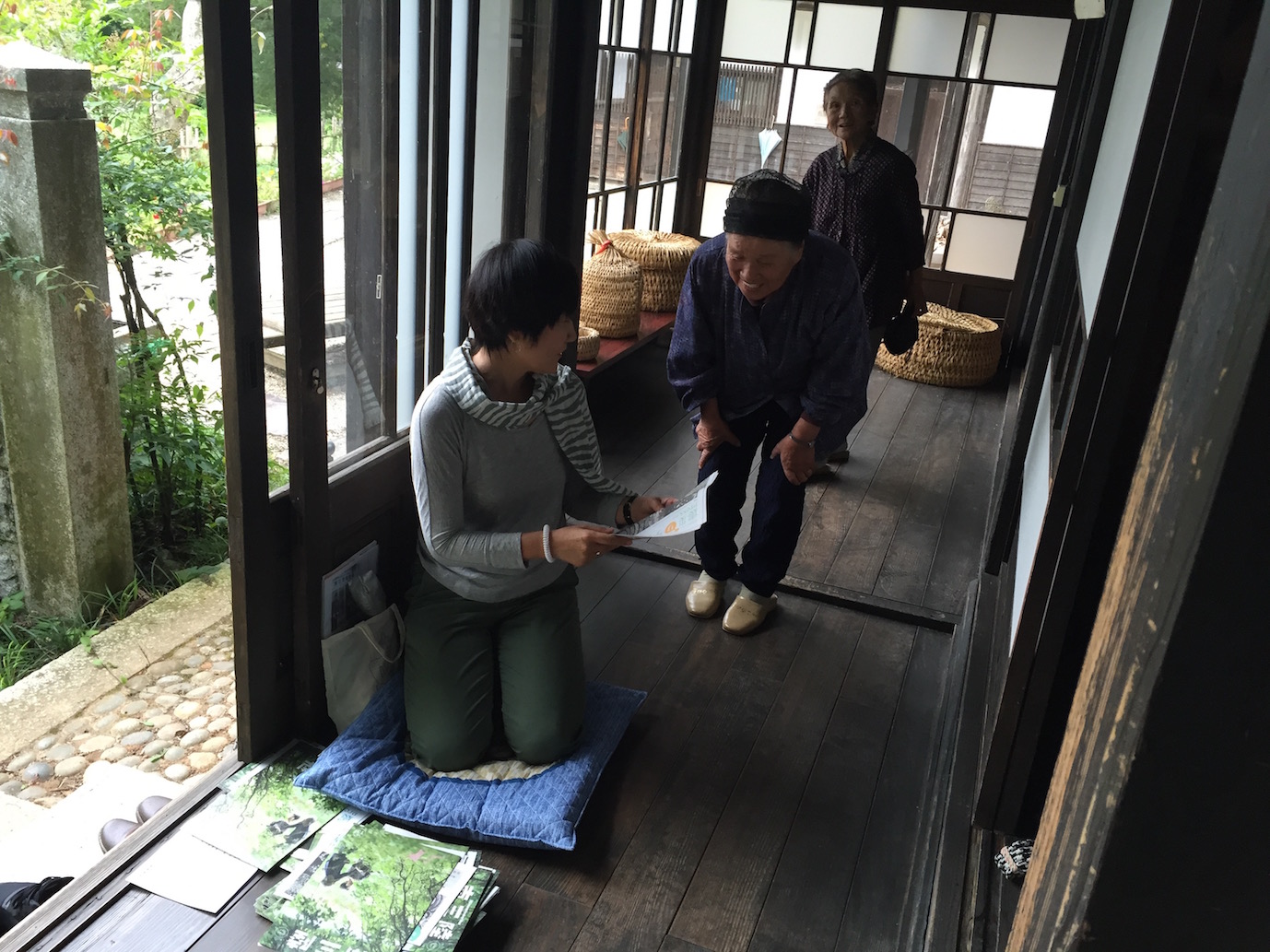

I have been conducting free screenings of Storytellers in the costal areas of Tohoku. For the 6th September 2015 screening in Iriya, Minami-sanriku, Yoshikawa helped me find a location, and on the day helped with preparation and on reception. This photo shows Yoshikawa at the screening venue.

The Destroyed Town of Warsaw

Poland has an area equivalent to about four fifths of Japan, and its population is around 38 million. This flatland country, sharing borders with seven other nations, has often suffered invasion from neighboring countries, and its name even disappeared from history for about 130 years. In the 14th century, many Jewish people emigrated there, and before the Second World War, synagogues―Jewish places of worship―numbered nearly 100 in the capital city, Warsaw, alone. Poland was occupied by Nazi Germany, and is known to have been the site of many concentration and extermination camps like Auschwitz, which carried out the extermination of not only Jewish, but also Polish and Gypsy people.

We visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau Former Concentration and Extermination Camp, the Warsaw Rising Museum and the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, places where the struggles of citizens are documented. We found, in all of these institutions dealing with the disasters of war, that art had somehow existed alongside tragedy―in the forms of songs, painting, sculpture and acting.

The rail track entering the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp

I saw paintings and sculptures by the people who were incarcerated in Auschwitz. In a café for the resistance that fought in the Warsaw Uprising, music bands played, and theater performances were shown. These are all cultural art expressions that are so ordinary in times of peace. On top of that, there were many documents published during the war, including newspapers, magazines, photos, diaries, letters and films that are preserved in these museums. Many records of memories to be handed down to the present day are exhibited with detailed explanation.

The tragedy of war is different from that of natural disasters. However, what is common is the fact that daily life is uprooted and deprived without reason. Human beings are the cause of wars however, so they could even be said to be natural disasters in a sense. Just as wars can continue for a long time, natural disasters are not really tragedies of a single day, even though, as with 1.17 or 3.11, they are often iconized that way. From that day on, loved ones have been taken away, and the situation lasts for a long time, while people have to commit themselves to the difficult battle of restoration.

The shore of Karakuwa, Miyagi

Now, it is 21 years since the Kobe earthquake, 12 years since the Chuetsu earthquake and 5 years since the Tohoku earthquake. There may be individual differences, but “that day” and “before that” are not the same, and there are many people continuing to struggle.

I cannot define art precisely, but if “expression born of the relationship between people and their world” can be describe art, then there are such expressions in everyday life, though they are not called art. People live as part of the world, and expression is inevitable, regardless of form. As a trigger to support or restrain expression, art has endless possibilities. If the artist grasps the idea that art exists in these expressions of life rather than as an occupation, then the possibilities of art in disaster―an extension of daily life―are as numerous as lost time, memories and things. If artists are to call themselves professionals of expression, they first need to associate themselves with the location of the disaster directly―in other words going to the place and absorbing everything that is there. Then, artistic expression will be drawn out naturally. There is no correct answer of what to do. Before thinking, why not visit the site?

Relation to Disasters, Records and Expressions

I spent my youth in Tohoku, living in the areas where many of my friends later suffered. After the Kobe earthquake, I was frozen, but in the spring of 2011 I went to the coast of Tohoku. I was distraught at the idea that there was so little impact my contribution could make, and felt like giving up. But perhaps that is why I could step forward, as Mr. Nagata said at the beginning of this series of essays. People’s lives had been uprooted and taken away – and perhaps this was my excuse to go to the site of the disaster, now I think back, looking for somewhere I could contribute my skills as an editor. I began to help as a middleman or intermediary, and through various encounters became able to publish a newspaper called Shinsai Regain Press. It has been almost five years since then. I was determined to continue my activities with the newspaper, and at the end of 2015 I set it up as an NPO corporation. I am aiming for it to be fully certified within two years.

The 16th issue of the Shinsai Regain Press is due to be issued on March 16, 2016. It has been a full 4 years, and we have distributed 40,000 papers nationwide, free of charge. For \250 a month you can subscribe to get 10-20 prints of every issue, which are released 4 times a year. We ask these subscribers to distribute the prints to the people around them, to gradually raise awareness of prevention and reduction of disasters, in the hope that when unexpected situations arise there are as many possibilities as there can be to survive them. There is also an e-book version available.

http://kyushu.ebpark.jp/book/smart/index/category/cate/329

At first, deeply impressed by all of the “people who take action” to support Tohoku―whether individuals or groups, from the area or from far away―I wrote articles about them, and sometimes also played a supporting role as an intermediary myself. From the second year onwards, I have been researching about how administrations, corporations, individuals and NPOs act in response to earthquake disasters all over Japan. And I really came to feel that, through my coverage and other intermediary work, the one who was given the opportunity to learn and was continuously encouraged was me myself. Pursuing this project is my way of repaying their kindness.

The NPO corporation Shinsai Regain works as an intermediary for individuals affected by disasters, and companies or NPOs who are in need of support, as well as publishing the Shinsai Regain Press. Cooperation with artists is one of our activities, and we have also been working on our own project in the Tohoku costal areas, ‘Recollect’, in which we aim to record memory. This project is being done together with photographer Toshie Kusamoto and filmmaker Rodo Izumiyama. Shinsai Regain website.

As an intermediary, we have helped people in various positions, working in various fields. Our support of art began with a chance personal encounter, and since then we have provided a lot of assistance.

One example is a documentary film project called the ‘Tohoku Documentary Trilogy’ that I took part in as a producer. The starting point was a film called The Sound of the Waves, produced as a collaborative project between the Tokyo University of the Arts and Sendai Mediatheque. The director, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, saw the unending footage on TV and YouTube and decided to go to Tohoku “simply to see what [was] happening with [his] own eyes.” Together with co-director Ko Sakai, who arrived in Tohoku a little later, The Sound of the Waves was completed in a few months, with the hope that it would “become a film that would still be around in 100 years.”

At that time, a center for remembering 3.11 was already up and running at the Sendai Mediatheque, and they had accepted the directors, although they still had some reservations about the idea of making the issues around the disaster into the medium of a “movie”. However, seeing the directors at work, discussing in the most sincere attitude and trying to record the voices of the subjects in their own unique way―as well as seeing them working with Kazuko Ono, a storyteller from Miyagi, they gradually began to trust them.

It was at that point that I got to know them. They were feeling that there was still more to shoot, and that they needed support. Through our organization, I was able to connect them with silent voice, a small film production company with the concept of listening to quiet voices. I saw The Sound of the Waves, and empathized with it. I approached Takashi Serizawa, a co-producer at silent voice, about supporting them and he had no hesitation―at least none that I saw. As a result, three films―Voices from the Waves KESENNUMA, Voices from the Waves SHINCHICHO and Storytellers – were completed, and together with the original, The Sound of the Waves, were made into what became known as the “Tohoku Documentary Trilogy”, which is still being screened in many places in Japan.

“Tohoku Documentary Trilogy” dir. Ko Sakai/Ryusuke Hamaguchi, 2013 © silent voice, distributor: silent voice

All of the films from the trilogy were submitted to the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, where Voices from the Waves and Storytellers picked up awards.

Process and Record, Reflection and Examination

How was the process of film production for the people affected by the disaster? What role will the film play in the future? There are many things that are unknown to me, and I assume that over a long period of time they will come to be understood, or remain mysterious. I do not know, but I continue to think. And the films are screened in and out of the country, even today. Hopefully, through the work of the directors, understanding of the disaster that extended into daily lives will be projected onto people living ”now”, removed from it by a long distance and time.

In March this year, it will be screened in South Korea and Germany.

One day I heard that one of the interviewees in the film murmured to the directors: “You shot it in the film, and I talked about it all here, so I can forget it now, can’t I?” During the busy period of restoration, this person was feeling guilt and anxiety about the idea that their memories were gradually fading away. “It was such an extraordinary thing, but I cannot remember it all. But, in the film, I can transcend time and space and hand down my memories forever” they said in relief. It is not easy to come to a full understanding of each person’s emotion regarding their experience of the disaster.

Over five years, among the many other art projects and other activities that took place, some ended and some continued. Regarding what was good or bad, there should be much discussion. Such reflection must always be done, and any looking back should be documented and examined as a lesson for the future.

In “Shinsai Regain Press #15” we documented a project in which we acted as an intermediary between local people and architects as they relocated their higher ground evacuation area. We entered an examination process to use the experience for the future.

Looking back, reflecting and examining is all a result of taking action.

I think it was when the film was screened somewhere: the directors who filmed The Sound of the Waves and Voices from the Waves described how they visited their subjects to listen to their stories without a camera and, through many conversations built a human relationship. Then they brought a camera to shoot conversations with their close friends from a unique angle, and edited it. This edited footage was then shown to the interviewees and, after cutting any parts that the subject didn’t want to be included, shown to them again. The production was done very sincerely, with repeated explanations of the risks that are inherent to the nature of film―the fact that many unknown people would watch the footage from any place at any time, and the violence of the camera. And the film was made ensuring the subjects understood those things. During this careful process, Ono quietly asked the directors “are you doing this to avoid responsibility? Even if you explained it 100 times there are some things that we, as amateurs, would not understand. And if we get hurt, would you just say “We explained it” and think it is okay?”

The answer would be “no, it is not okay”. The directors are well aware of that too. What these two directors have learned from the “Tohoku Documentary Trilogy’ is immeasurable.

Kazuko Ono’s attitude and policy of “listening” cannot be described in this limited space, and I don’t believe I could ever fully express it, but I urge you to meet her in the film Storytellers.

An Affirmation

By nature, we are all small and powerless, but we always affect the world in one way or another, whether we do anything special or not. We are alone, but cannot remain alone. We live our lives with potential for every eventuality, good and bad. And even what we can say are good or bad are not individual events, but depend on others, so it is not easy to see what they are.

Based on that assumption, I would first like to affirm all of the people who went and took action in Tohoku due to their empathy after the Tohoku earthquake. I want them to retain the feeling of being impelled to act as living beings. However, it is also important to accept the phenomena created by the action as much as possible, regardless of whether that is possible or not. It is not anything especially special or courageous. Rather, it is an extension of daily life. As long as we live, day by day our existence creates some kind of impact: we just have to live on and confirm it―being pleased, giving pleasure, and indeed hurting others and being hurt. There may be some things that do not go well. But reflection is what it is precisely because an action has been made, and there are many prior actions that lead into the future. I do not wish for the word “possibility” to have a negative connotation or to shut things down. I myself have a lot of regrets, and have even felt bitter at times, but I am the sum of those parts.

It is difficult to live without learning to embrace life itself and surrender to it. I wish to embrace the vagueness, diversity and weakness within myself and so value all living people. Some people may say I am strong, but in fact it is the very opposite: I am very fragile. But because I am fragile I make an effort to live with others, accept failures, forgive and be forgiven. This is completely normal, and obviously important in our daily life, and I hope for it to be the foundation of prevention and reduction of disasters, and restoration after them.

This is a poster that is very important to me, and I keep telling people about it. It shows a saying of an African indigenous people.

“Many small people in many small places, do many small things, that can alter the face of the world.”

The poster is a co-creation by Werner Penzel and Yoshie Nanno.

From “Listening”

I do not believe that I could be anywhere near being able to answer the questions of the possibilities of art in disaster even with all of these words, but I would like to give my whole-hearted appreciation, as someone born in Tohoku, to all of the artists who visited from far away. It was so important that they came and listened. The truth is, there was not much they could do, and instead they learned a lot from the area, items there and from the people who suffered in the disaster. So it was these visitors who drew in the energy of life. The difficult experiences the local people recounted may have been painful, but at the same time they led to the power to live, and can contribute in future disasters. So I hope people, not only artists, will visit the area and listen to the voices of the people who are still struggling five years on.

There is no correct answer. If you mess up, you put your head down to reflect and start again. You can be still and keep thinking, or you can not think at all. If you are living your own life, that is all. And if I can be wishful, you may be prepared in your daily life for disaster, which might strike you the next time.

In Poland I saw many records of the lived memories of people who lost their lives in concentration camps, ghettos, and the Warsaw Uprising. And I have learned a lot through coverage of the earthquakes in Tohoku, Kobe, Chuetsu and Iwate and Miyagi. I am destined to live with my family and friends, while listening to the voices of people, in Poland or Japan, who live the present after experiencing great hardship, and to think of my friends who passed away.

Life is short―just a few decades.

I want all people to live without harm. This wish, and the starting point of my activities, is so simple that it may sound ridiculous, but that is it. The pleasure of listening, talking and expressing is built upon living.

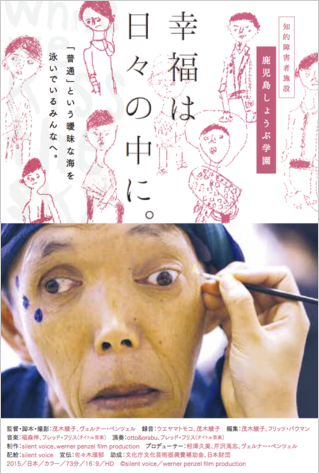

In June 2016, at Theater Image Forum in Shibuya, we open a new film that records five years in Shobu Gakuen―a facility for mentally disabled people ―in Kagoshima. It is co-directed by Werner Penzel and Ayako Mogi, and produced by silent voice. Shooting began a little before the Tohoku Documentary Trilogy, and its production took place concurrently with it. In those days, I felt that I myself, going up to Tohoku regularly, was supported by the production of this film in the same way that expression and living are directly connected in those with mental disabilities.

The English title is While We Kiss the Sky. Why this title? Come and see the film to find out.

February 29, 2016

Net TAM memo

From this issue onwards, “The Possibilities of Art in Earthquake Disaster Reconstruction” will be widened as a framework to “The Possibilities of Aart in Disaster”, signifying a new start. Last issue, the interviews with the NLI Research Institute Art and Culture Project’s Torao Osawa and Plus Arts’ Hirokazu Nagata brought new perspective, moving “earthquake disaster” to “disaster” and also drawing “prevention of disasters” into the contents. The thoughts on “the possibilities of art” began with the Tohoku earthquake. Along with the people who contributed to this series of 16 articles, and our readers, we will continue to think about the possibilities of art affecting the whole of society in a newly developed phase named “Disaster”.